States with the best sex ratios, gender indices elect the fewest women to Parliament.

New Delhi: States with the best sex ratios and gender indices elect the fewest women to Parliament, finds a study conducted for Mint by IndiaSpend.com, a data journalism initiative. Conversely, states with poorer gender indices have the highest percentage of women Members of Parliament (MPs).

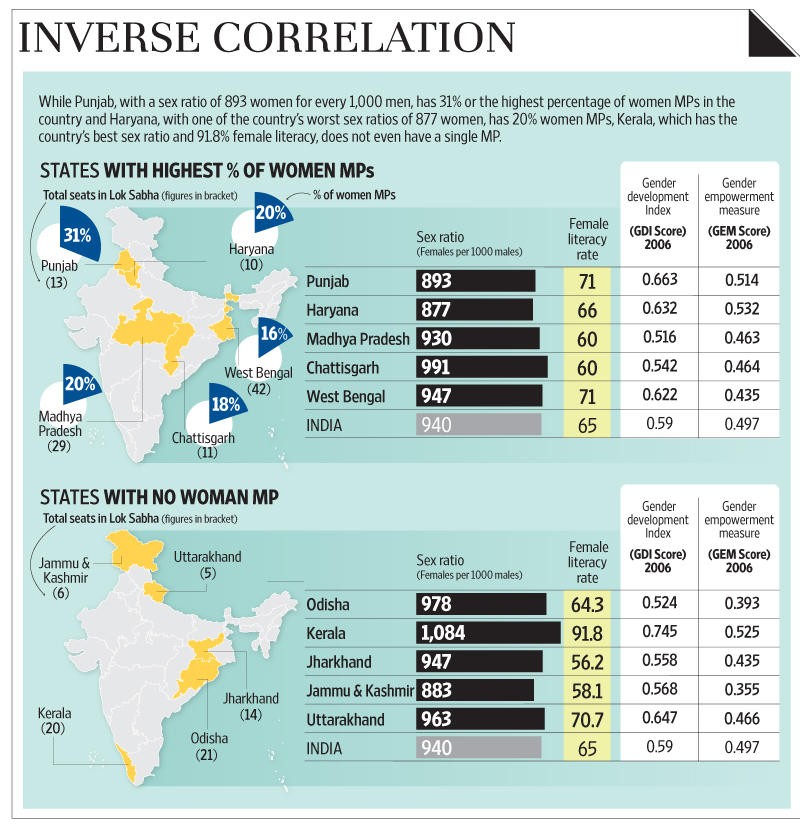

The top five states with the highest percentage of women MPs are, in order of ranking, Punjab, Haryana, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh and West Bengal.

Punjab, with a sex ratio of 893 women for every 1,000 men, far below the national average of 940, as per the 2011 Census, has 31% or the highest percentage of women MPs in the country. Haryana, with one of the country’s worst sex ratios of 877 women for 1,000 men, has 20% women MPs, finds the report.

On the other hand, states that do well on gender tend to have poor representation of women in Parliament. Kerala has the country’s best sex ratio of 1,084 and 91.8% female literacy, and has 20 Lok Sabha seats. None is occupied by a woman.

In fact, several states across India elected no women in the 2009 general elections. Amongst the larger states are Odisha, Jharkhand, Jammu and Kashmir and Uttarakhand. In 2012 when Vijay Bahuguna became Uttarakhand chief minister, the Bharatiya Janata Party’s Mala Rajya Laxmi Shah, daughter-in-law of Manvendra Shah who represented the Tehri Garhwal seat eight times, won the bye-election and became the state’s sole woman MP.

The representation of women is just as dismal in the state assemblies. None of the five states that went to the polls last year—Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Rajasthan, Delhi and Mizoram—elected more than 10% women. Mizoram, in fact, has not had a woman MLA for the past 10 years.

Conducted by Saumya Tewari, the report also finds that a large proportion of women MPs are backed by politically well-connected families. In Punjab, for instance, of the four women MPs—two from the Shiromani Akali Dal (SAD) and two from the Congress— three have family ties in politics. Harsimrat Kaur Badal of SAD is the wife of party president and deputy chief minister Sukhbir Badal, Santosh Chowdhary of the Congress party is the wife of former state lawmaker R.L. Chowdhary and Preneet Kaur of the Congress is the wife of former chief minister Amarinder Singh.

“Ther

e is no connection between development and the growth of women’s leadership,” says Ranjana Kumari of Women Power Connect that works towards creating women-friendly legislation. “In the backward states, men are opposed to women’s reservation and the only women who advance are women they can control.” Agrees Tewari, “If you look at the number of women getting elected in the more backward states, you will realize that most are proxies for male politicians.”

The IndiaSpend.com report is nuanced by including two parameters: the gender development index (GDI) and the gender empowerment measure (GEM) of 2006, the last year both were measured. The GDI looks at health, including infant mortality and life expectancy, education and income and standard of living among women. GEM has three parameters: political participation and decision-making, economic participation and decision-making and power over economic resources.

Jammu and Kashmir is perhaps the only exception that fares poorly on gender indices and also does not have a single woman MP among the six that represent the state. The state has a sex ratio of 883, female literacy of just 58.1% and a GDI ranking of 0.568 and GEM of 0.355, the lowest amongst the states studied.

The findings of the IndiaSpend.com report ties in with a recent Brookings India report, Missing Women in Indian Democracy by Shamika Ravi that finds women are more likely to contest elections in constituencies where the sex ratio of electors is worse. In other words, states like Haryana and Punjab are far more likely to see women candidates than, say Kerala and Tamil Nadu. In states with a higher sex ratio, women seek representation through voting.

Moreover, continues Ravi’s report, women have lower chances of winning elections in constituencies that have a low sex ratio. So, two things happen. First, women don’t contest in socially advanced states. And second, women contest from socially backward states but don’t win.

Worldwide, as of 1 January, women occupied 21.8% of all parliamentary seats, according to data available with the Inter-Parliamentary Union. For Asia, the figure is 18.4%, worse than sub-Saharan Africa, where women make up 22.5% of all parliamentarians.

India’s 11.4% representation of women in the 15th Lok Sabha is lower than even the Asian average. In a ranking of 189 countries, the world’s largest democracy figures at a poor 111, below such neighbours as Nepal (rank 36), Pakistan (72) and Bangladesh (74).

The need for greater representation is perhaps underscored at a time when women voters are increasingly turning out in larger numbers than men to cast their ballot.

While male voter participation has remained unchanged over time, the sex ratio of voters—the number of women voters to every 1,000 men voters—has increased from 715 in the 1960s to 883 in the 2000s, finds the Brookings India report.