The coronavirus pandemic has highlighted an old problem of the mistreatment of women in the labour room

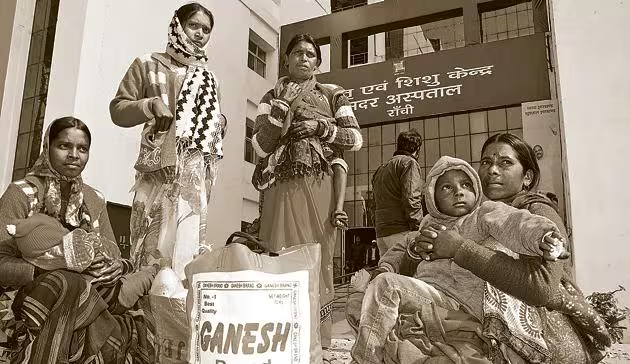

The mistreatment of women in the labour room is fairly common, especially if you’re poor(Diwakar Prasad/ Hindustan Times)

Don’t touch me, the nurse yelled at the woman who was about to deliver her second child. On March 26, when the woman went into labour, fears of the coronavirus were high at the community health centre in Atraulia, Azamgarh. The Dalit wife of a daily wage labourer was made to wait outside until it was time to give birth. “Even then, the nurse refused to touch her, leaving the delivery to the dai (midwife),” says Sunita Singh, a social worker with Sahayog, an NGO that works on women’s health rights.

The mistreatment of women in the labour room is “fairly common, especially if you’re poor,” says Singh. The violence from midwives, cleaning staff, nurses and even doctors ranges from abusive language and sexualised comments to slapping and forcing women into birthing positions.

“There’s a clear power asymmetry that involves money, caste and class,” says Jashodhara Dasgupta, senior advisor, Sahayog.

The pandemic has underlined an old truth about labour room violence. On June 6, Neelam Kumari Gautam died during labour after being turned away from eight hospitals. At the first hospital, the doctor reportedly told her: “I’ll slap you if you take off your mask.”

In Hyderabad, a 22-year-old developed post-partum lung infection and died when no hospital would admit her. And in Uttarakhand, a pregnant woman delivered twins at home after being refused admission by five hospitals. She and her babies died a few days later.

A 2020 report, Human Rights in Childbirth, finds that pregnant women, especially those from marginalised communities, bear the additional load caused by strains on health systems. The World Health Organization warned recently that women are at “heightened risk” of dying at childbirth.

To meet the Millennium Development Goals on maternal mortality ratios (MMR), government schemes since 2005 have, through cash transfers, pushed for institutional birth, bringing MMR down from 370 per 100,000 births in 2,000 to 145 in 2017. The number remains unacceptably high, but “is a big achievement,” says Aparajita Gogoi, executive director, Centre for Catalysing Change, an NGO that works with women and girls. “Now we need to focus on quality.”

A 2015 study of 275 mothers in three Uttar Pradesh districts found that all had experienced at least one indicator of mistreatment — from being denied a birth companion to being yelled at.

Launched in 2017, the national Laqshya programme’s goal is respectful maternity care. It lists dos and don’ts for care-providers: No verbal or physical abuse, not leaving women unattended, providing privacy and taking consent before examinations and procedures. Reducing MMR is an incomplete goal unless there is an improvement in women’s experience of childbirth; an experience that does not put the priorities of health providers over birthing women, reducing them to passive participants.

If women are to put their faith in health centres, they must be assured of respectful and dignified treatment.

Namita Bhandare writes on gender

The views expressed are personal