Perhaps the biggest transformation has taken place in rural India where in 2016, 70% of 18-year-olds were already in college. But do they want daughters to pursue careers? That’s another story.

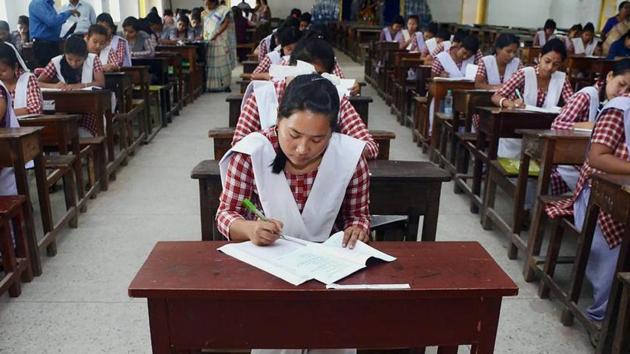

The surge of women and girls in education is an ongoing trend that every year makes tiny, but significant, gains(PTI)

The surge of women and girls in education is an ongoing trend that every year makes tiny, but significant, gains(PTI)

To call Sunita Khokar’s resume impressive is an understatement. Khokar, the daughter of a farmer who never saw the inside of a classroom, has a list of degrees that includes three MAs (economics, political science and sociology), a B.Ed, an M.Ed and an MPhil. And, yes, she’s currently working on her PhD.

Khokar, 41, married with two children, would certainly figure in the government’s latest findings on higher education where the gap between women and men is at its lowest. Female enrolment in colleges is up from 47.6% in 2017-18 to 48.6% in 2018-19, the All India Survey on Higher Education found. In Uttar Pradesh, there are 90,000 more women than men in higher education.

The surge of women and girls in education is an ongoing trend that every year makes tiny, but significant, gains. In 2015, Mint did a series of articles that documented how girls breached the gender gap in primary and secondary school, with a gap of just 0.8% remaining at the class 10-12 level.

That generation of girls is now headed to college. This is reflected in the growth of universities from 903 in 2017-18 to 993 for 2018-19.

The success of this often unsung revolution is partly to do with targeted government interventions including scholarships, subsidies, and quotas for women. And partly, it is due to aspiration and easier access to technology and information in the post-liberalisation era, says educationist and writer Meeta Sengupta. “Mothers who’ve had an education are clearing the path for their daughters,” she says. “Role models and support from within colleges and schools are enabling women to take the next leap.”

Perhaps the biggest transformation has taken place in rural India where in 2016, 70% of 18-year-olds were already in college. The Bhagat Phool Singh Mahila Vishwavidyalaya at Khanpur Kalan in Sonepat district is the only all-women’s university in Haryana with two campuses, hostels and several colleges including for engineering, law and teacher-training. With 7,000 students, it caters largely to women from adjoining villages, many of them first-generation learners. “There is a huge change in demand. Parents now want their daughters to study,” says vice chancellor Sushma Yadav.

But do they want daughters to pursue careers? That’s another story. A January 2019 study by the Azim Premji University found that 96% of parents said education was as important for girls as it is for boys, but only 52% saw it as a means to employment for daughters, whereas for sons, it was 71%.

Educated women are a force for change. They are likely to marry later and have fewer kids. Yet, without social support structures for careers, education is in danger of becoming a goal in itself. Female labour force participation has plunged to 23.3% according to the 2018 Economic Survey. More girls are studying, but they are not necessarily landing more jobs.

Khokar says she plans to work — eventually. Meanwhile, her daughter is swotting for the medical school entrance exam. Her role model? Mum, of course.

Namita Bhandare writes on gender

The views expressed are personal